03 Dec Margaret Dugger’s Perspective on Mentorship

This blog is written by Margaret Dugger, Session 1 Weaving mentee. Read Margaret’s story about her experience on campus below.

My experience at the Folk School left my heart renewed. The mentorship program was a unique opportunity, and in a year of cancellations, it was a breath of fresh air. I applied to it because I wanted the luxury of being a student: studying history, taking an in-depth look at a few topics, and being able to weave for a month with other weavers. I am at a stage in my career where it feels best to apply to everything I am qualified for and to run with any opportunities given. I ended up falling in love with the Appalachian Mountains again and learning so much about what I thought I already knew.

The weaving mentorship session lasted a month, split into four classes, one for each week. The first week was focused on a specific period of history for the region: the settlement schools of the Appalachians that revitalized weaving and other crafts that were disappearing. Settlement schools were around during the late 1800s and early 1900s as the Industrial Revolution made machine-made fabric more affordable. People stopped weaving their clothing and took apart their looms. The isolation of the Appalachian Mountains slowed the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution, and handweaving remained commonplace there for longer than in most parts of the U.S. In the late 1800s, educated women from the north began coming to the region aiming to be of social service to its people.

They opened many settlement schools, hoping to provide a way for the locals to better themselves by income via weaving, education, resources, etc. Many of the settlement schools found their focus to be revitalizing craft traditions for locals to be able to provide additional income for themselves. The settlement schools would collect and sell the goods to those who could afford them and wanted to support the cause. This activity played a large part in saving a disappearing art of weaving that had developed in the isolation of the region.

The Appalachian people of the craft revival period were resilient and held fast to their traditions. They found a way to make their isolated way of life work for them without having to sacrifice their solitude. In a world that was moving quickly away from self-sufficiency, they found a balance by remaining at their homes and finding ways to bring extra money through weaving.

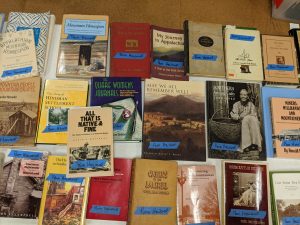

A sample of Pam Howard’s incredible book collection

This week felt like my brain cracked wide open. The entire week (or month) could have been spent reading about this subject. Pam Howard, the instructor for the week, brought her encyclopedia of knowledge and a small library of books and research she had done on the subject. I was blown away. I learned to weave in a 2-year program at Haywood Community College in Clyde, North Carolina, which resides in the southern Appalachians. Before that, I spent a large part of my childhood in Mitchell County, also part of the region. I naively thought I knew more than I did about the place I live in and love so dearly.

While learning about the history from Pam, we also spent time weaving replicas of items and patterns made by women during this period. Going through the same processes through direct experience was an important part of learning that would continue through the week. I find great significance in learning through replication, which is a touchstone of the craft process. You learn by doing. To be able to work through the same patterns with new information and new eyes is one of the things that keeps weaving vibrant.

A scarf in progress using the traditional honeysuckle pattern

This experience continued into our second week, which was the overshot class taught by Susan Leveille. These classes blended perfectly together. Overshot patterns are ancient and widely used in many cultures throughout the world but developed to have their distinct look in this region. Historically, overshot patterns were used to make coverlets or bedspreads for the household.

About Margaret Dugger

Margaret was born and raised in Charlotte, North Carolina. Having originally been interested in music, she attended school for performance in classical cello with a focus in early and baroque music. She took up knitting and moved to Western North Carolina in order to study textiles at Haywood Community College where she received her associate’s degree. Margaret’s work has been part of the Southern Highland Craft Guild shows, been on display at the Folk Art Center in Asheville, Blue Spiral 1 Gallery, and in the Shelton Museum of Craft. She currently lives in a cabin in the mountains with her partner, making work from her home studio.

Overshot coverlets woven by Cassie Dickson

Discussing antique coverlets

Before the Industrial Revolution, they were made from hand-grown linen or cotton, handspun and woven together with wool from their sheep that they spun and dyed themselves. They were a feat of labor, self-sufficiency, and incredible works of art. Susan mentioned several times the idea of a one-room log cabin with a coverlet on the bed, an image that is still sticking with me several months later.

Getting to know overshot by making samples

For the third week, we brought our class a little closer to home by studying the techniques of a Folk School employee Alice Tipton. Alice Tipton was the kitchen manager of the Folk School during the mid-1900s and lived in the area throughout her life. While being employed and raising several children, she found time to weave astounding mountain landscapes using an uncommon tapestry technique. We spent the week looking closely at her works in person, loaned to use from family members and the archives of the Folk School. We wove both replicas and our creations during the week, using incredible naturally dyed yarn that our teacher Tommye Scanlin had dyed herself and brought for us. The quiet meditation of the week was a nice contrast to the faster and louder weaving of the first two weeks. It was my first time paying attention so closely to the landscape and taking the time to translate it into something physical. It felt like a kind of luxury that will stick with me for the rest of my life. In my walk to and from the studio every day, I thought about Alice Tipton taking her walk to and from work, looking at the same mountains, and going home to weave just as I was.

One of Alice Tipton’s weavings

One of my weavings using the Alice Tipton technique

Week 4 with Kathy Tinsley was spent learning to weave rag rugs. Rag rugs are probably the oldest technique that we learned during the month. They are made by using cut up strips of cloth, woven in to make the bulk of the cloth. Rag rugs previously were made with any scraps of rags or fabric that were too far beyond repair. Old cloth would be recycled to make a new, useful, and functional item for the household. Rag rugs were kept on not only floors but beds and walls or anywhere else that needed added insulation in colder climates. Now, they are often made from bedsheets or t-shirts with weavers creating more specific designs and color combinations. This class was a thrill. We experimented with using different kinds of cloth to cut up and weave with different colors of thread to change the overall look. We had switched from small and meticulous tapestry to large and fast rug weaving, an exciting change of pace and a good reminder of the versatility of weaving.

Cut rag rugs for rug making

An ambitiously long rug taken off the loom on our last day

Classes were only part of the experience. Every day we had incredible meals prepared specially for us which we shared in the company of each other. Chef Jarrett and Chef Case, among the rest of the staff, took incredible care of us and made us full meals with different sides and desserts every day. I’ve never been so well fed in my life and probably won’t be until I’m back at the Folk School. I hadn’t realized how big of a difference it makes in my day when I don’t have to worry about making my next meal. I was able to dedicate extra hours of every day to learning and weaving because every single need was taken care of. Elizabeth Belz, the Creative Catalyst Fellow, went above and beyond anything that was required from her. To delivering food to us on the weekends, to organizing a wood fire oven pizza party, to giving everyone a mini blacksmithing workshop, and making sure we had autumn bonfires. Elizabeth did it all.

Delia during the blacksmithing workshop

The Brasstown scenery also affected the stay. Walking to and from the weaving studio, the house, and the dining hall, stopping in the garden to look for a ripe fig to eat from the fig tree: these parts of the campus had an impact on the experience.

The view from my bedroom window

Hannah walking home, becoming part of the landscape

The Folk School had a profound effect on me during a hard and tumultuous year. The month spent here, though short, reaffirmed my love of weaving and of the importance of craft and making in my life. It helped me to reconnect with the land that I know and love so much and strengthened that connection by giving me the chance to learn about the weavers who were here before me and whose footsteps (or treadlings) I follow in. I have been weaving in my home studio with more motivation and direction than I’ve had in a long time. As we slide into winter here I’m holding close to the tradition that this was the season for weavers of my area to dedicate the most time to the loom.

Session 1 mentees

About the Mentorship

The 2020 Traditional Craft Mentorship Program was a grant-funded opportunity for early-to-mid-career artists to spend a month at the Folk School, learning from master artisans. The unique situation of the Folk School closure due to COVID-19 allowed us to offer 6, 1-month-long programs, with 3 students per program, and 2-4 mentors working collaboratively and independently in studios. Subjects included: Basketry, Music & Dance, Weaving, Blacksmithing, Chairmaking, and Fiber Arts.

Pingback:Elizabeth Belz Reflects on Creative Catalyst Fellowship - John C. Campbell Folk School Blog

Posted at 12:39h, 10 March[…] that the Folk School will utilize moving forward with their strategic plan. This work included the Traditional Craft Mentorship Program, partnership programming with REACH (a local shelter), setting up weekday evening classes for […]