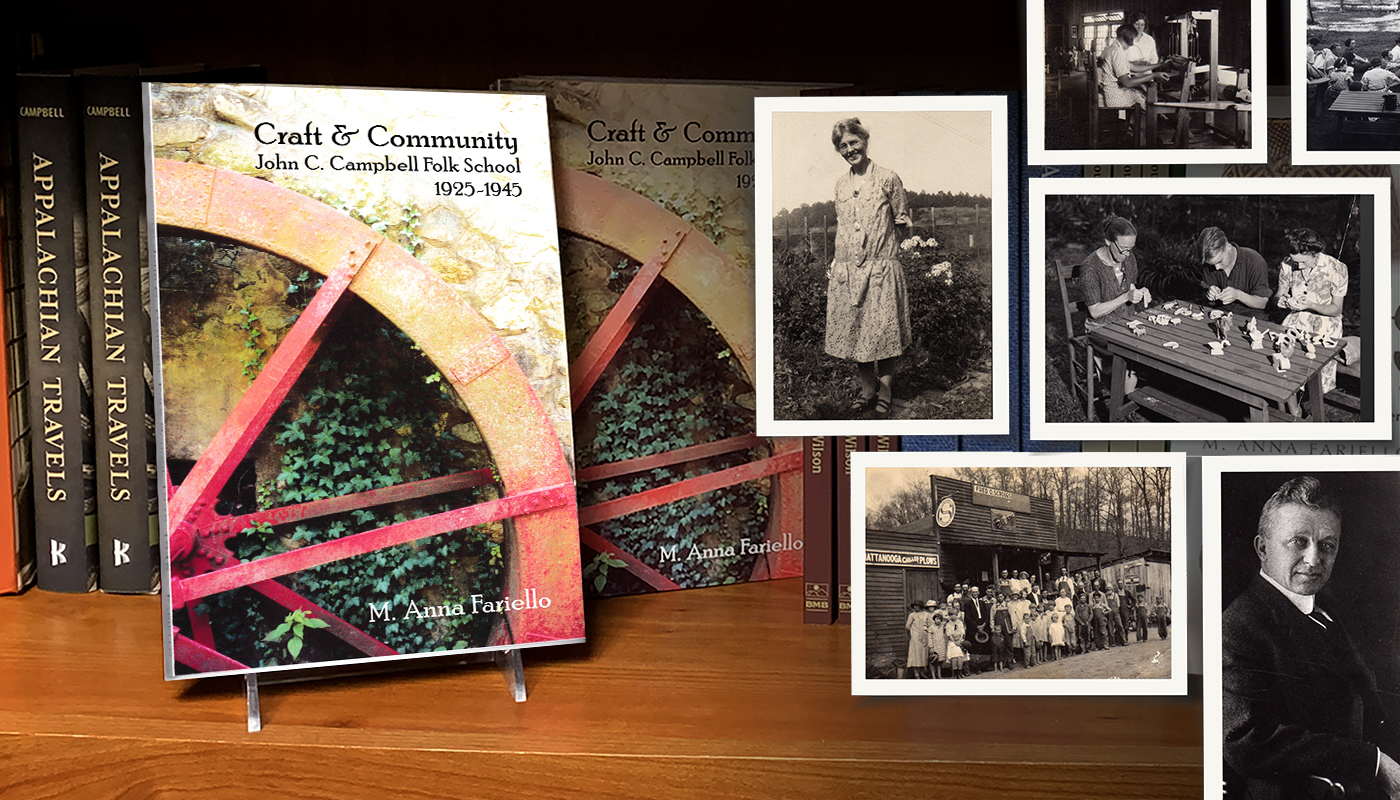

25 Nov Interview with Anna Fariello, Author of “Craft & Community: JCCFS 1925–1945”

If you love the Folk School and are interested in our history, I highly recommend curling up with Anna Fariello’s wonderful book, Craft & Community, which explores the first 20 years of the Folk School, with a focus on Olive Dame Campbell. Find Craft & Community in our Craft Shop, available in-person or online. Enjoy our interview!

Anna Fariello

CP: What is your connection to the Folk School?

AF: My interest in the John C. Campbell Folk School goes back to 1993 and the Year of American Craft. The National Museum of Women in the Arts hosted a conference on Women & Craft, where I presented on the women who drove the craft revival, a period of intense interest in the handmade that began at the turn of the 20th century. At the time, there wasn’t much published on these women and little was known of their broad impact on the region. I began with the “knowns:” Lucy Morgan, founder of Penland, and Frances Goodrich, founder of Allanstand, wrote their autobiographies. I knew and interviewed Marion Heard who was at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts in Tennessee. I considered these places together—along with Pine Mountain and Hindman Settlement schools—and thought I had a good topic.

At the time, I knew less about the John C. Campbell Folk School and, in fact, thought that it had been founded by John Campbell himself. Once I came to the knowledge that it was his widow, Olive Campbell who founded the school, I knew that I was onto something. I spent the next 10 years poking around regional archives, visiting the Southern Highland Craft Guild, Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, Berea College, and the Folk School. At the time, many archives were not organized; some were in dusty attics. Today, I am happy to say, that most of these organizations have since taken a good look at their histories and have preserved and processed their archival holdings.

CP: Speaking of archives, the Craft Revival Archive is so wonderful! What an amazing digital collection with so much content and information. It’s so great that the public can easily access and search through it. What was it like organizing the Folk School archives for the project?

AF: At this moment, I think that the Craft Revival Archive is greatly underutilized. Typically, universities don’t do much to “market” faculty research. The archive contains thousands of documents, photographs, minutes, and reports, a real treasure trove for anyone interested in this subject. When I did my research, and in deciding what items should go into the archive, I traveled to each of the physical repositories, poking into dusty bins in search of relevant historic materials. The access provided by today’s digital archiving is phenomenal.

Brasstown community in front of Scroggs store.

Brasstown community in front of Scroggs store.

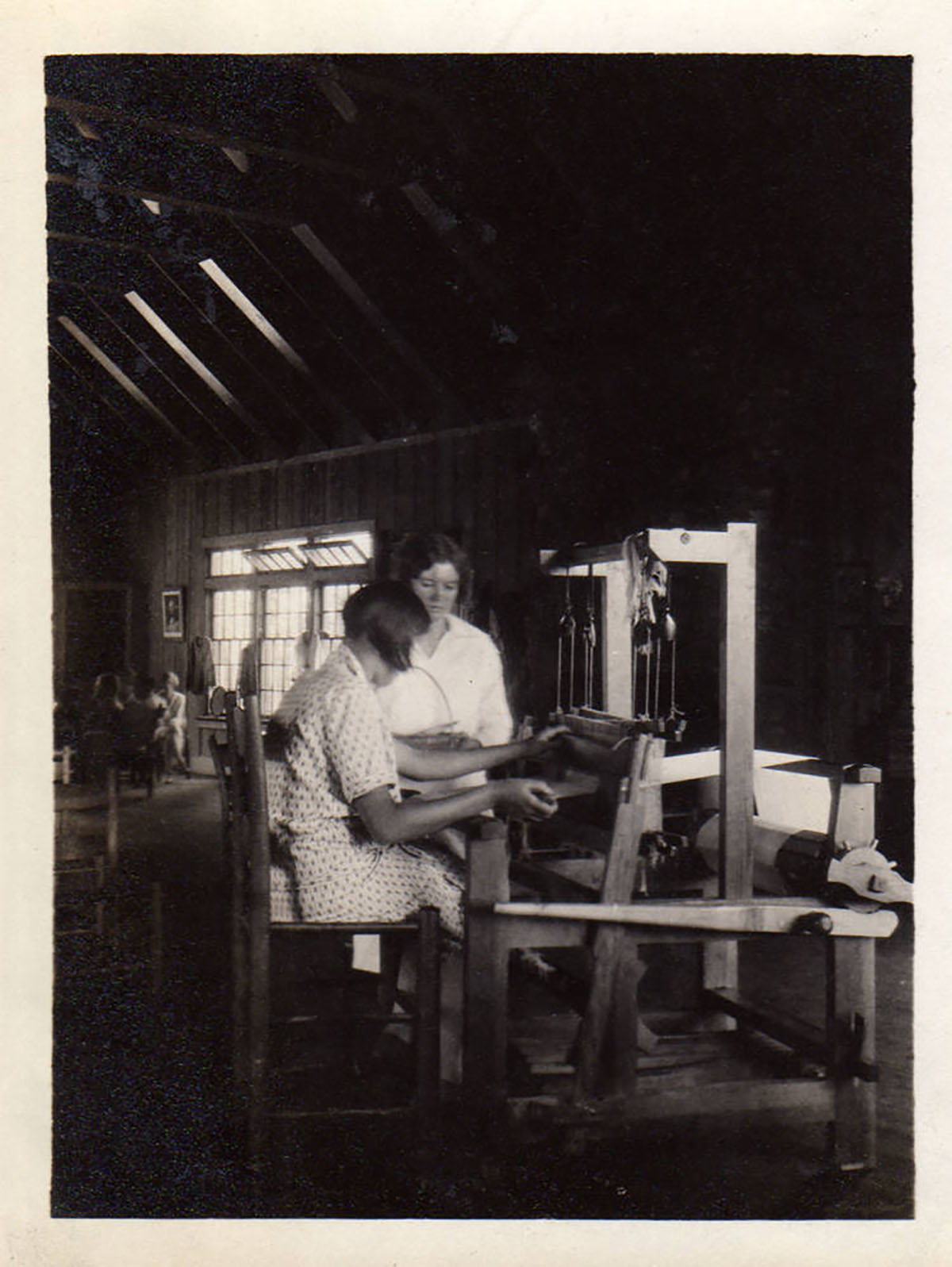

Students learning to weave in the Community Room

Students learning to weave in the Community Room

Carving wood while sitting on a fence

Carving wood while sitting on a fence

CP: Congratulations on your recent Lifetime Achievement Award from the Southern Highland Craft Guild! What do you consider to be your greatest achievement?

AF: In some ways, I think that my greatest achievement—perhaps I should say my greatest challenge—was my first book Objects & Meaning. When Paula Owen and I got the idea to publish a book on the history and theory of craft, no one had ever done that before. We struggled with selling the concept to a publisher. All of them thought of craft books as solely “how to,” so this book, in that way, was more ground breaking than the others. There have since been many books that focus on some aspect of craft history or theory but, in the early 2000s, this was rather unheard of.

AF: In some ways, I think that my greatest achievement—perhaps I should say my greatest challenge—was my first book Objects & Meaning. When Paula Owen and I got the idea to publish a book on the history and theory of craft, no one had ever done that before. We struggled with selling the concept to a publisher. All of them thought of craft books as solely “how to,” so this book, in that way, was more ground breaking than the others. There have since been many books that focus on some aspect of craft history or theory but, in the early 2000s, this was rather unheard of.

CP: Have you ever taken a class at the Folk School?

AF: My husband taught blacksmithing at the Folk School for many years and I often traveled with him. While he taught, I continued my work in the archives. While I didn’t take a class, I did get to experience life at the Folk School, participating in Morning Song, communal meals, and relaxing walks along meandering pathways. One of my most exciting memories is when we stayed in the Farm House in the very room that was Olive Campbell’s. I was already familiar with the house from historic photographs so, when I saw it, I knew immediately where I was.

CP: How did craft become such a big part of your life? Do you have a favorite craft?

AF: I studied both art and art history in college, but it wasn’t until the last semester of my senior year that I took a ceramics course. I had never worked in clay before and it was an immediate experience of connection. I spent 10 years as a professional ceramist, making pots, tiles, and sculpture. I began organizing exhibitions of my work and of work by other craft makers and, eventually, went back to school to earn a degree in Museum Studies and Art History. My career then took a turn toward research, writing, and curation.

CP: I love your book, Craft & Community. It was so great to finally learn more about Olive Dame Campbell’s life, vast accomplishments, and the origin of the Folk School. Why did you decide to focus on Olive and the first 20 years of the Folk School?

AF: With such a long and storied history, I knew that it would be impossible to write a comprehensive history of the Folk School. Besides, I was particularly interested in the ideas that lead to the school’s founding. I was also curious about the fact that the initial focus of the school was not craft, and I wondered how the school evolved to garner a reputation as a craft school. It was these topics that interested me most.

CP: How did you decide on your book title: Craft & Community?

AF: I thought long and hard about a title for the book, because I do think you can tell a lot about a book by its cover. I considered phrases like the school motto, “I sing behind the plow” and various quotes from Olive Campbell. In the end, I wanted to distill the characteristics of the Folk School into a few words. “Craft” was obvious as that was my focus, but as I thought more about this, I realized that an equal emphasis has always been community. From the very first local gathering, during which community members pledged land and labor to the school, to the school’s first Handwork Week, to the founding of the Brasstown Carvers, the Folk School has always looked to link itself to the people around it. In a Mountain Life and Work article in 1929, Campbell wrote, “Community and school are one.”

CP: Why did women play a large role in the craft revival? How has the role of women in craft changed since the days of Olive Dame Campbell?

AF: Women played a major role in the craft revival; in fact, one might say it was a women’s movement. Up through the late 19th century, higher education for women was limited. Those who attended college, after graduation, found themselves closed out of professional occupations. Some of the more adventurous among them struck out on their own, leaving the comforts of their upbringing to settle among poorer peoples and, inadvertently, making professionally rewarding work for themselves.

Appalachia is relatively close to northeastern cities and became a kind of “mission field” for those wanting to participate in what was then called the “uplift” movement. From my reading of their writings and diaries, however, I think that their purpose changed from an outward focus to the effect the work was having on themselves. Marguerite Butler is a good example. I think that her initial reason for moving to Kentucky was to work with the underprivileged but, once she got into the work, she felt personally empowered. No one really cared about these small rural communities; here, women could move into leadership roles and make their own decisions. This was not true of their home communities, in which they had responsibilities governed by propriety.

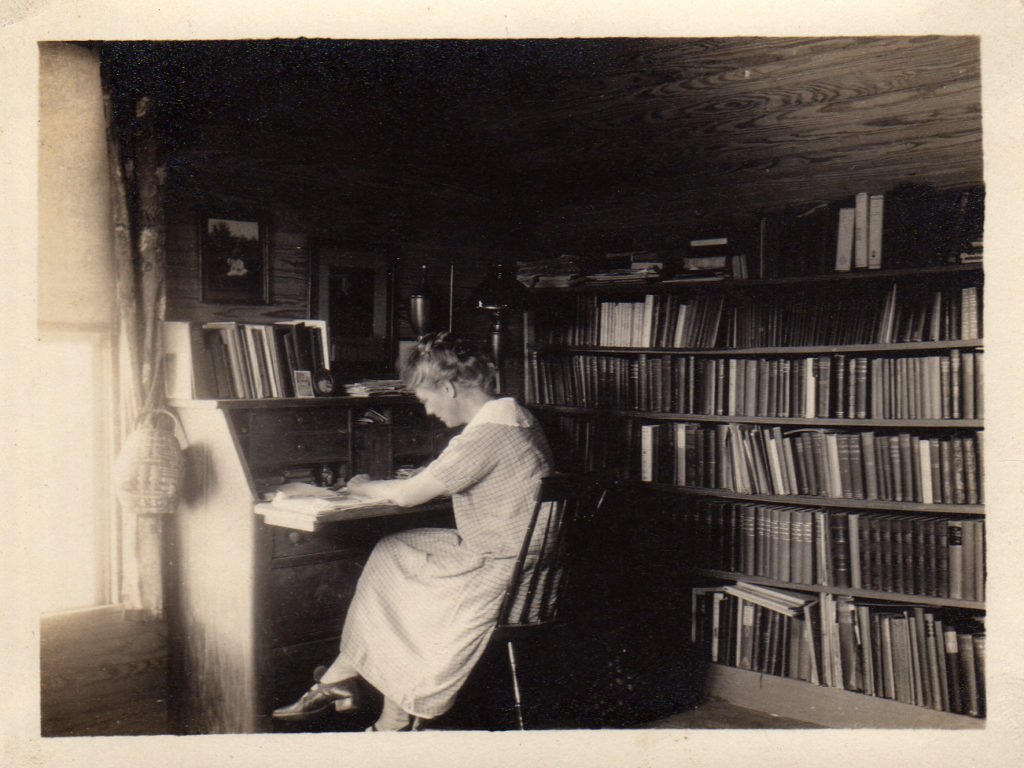

Olive Dame Campbell at her desk in her room in Farm House

Olive Dame Campbell at her desk in her room in Farm House

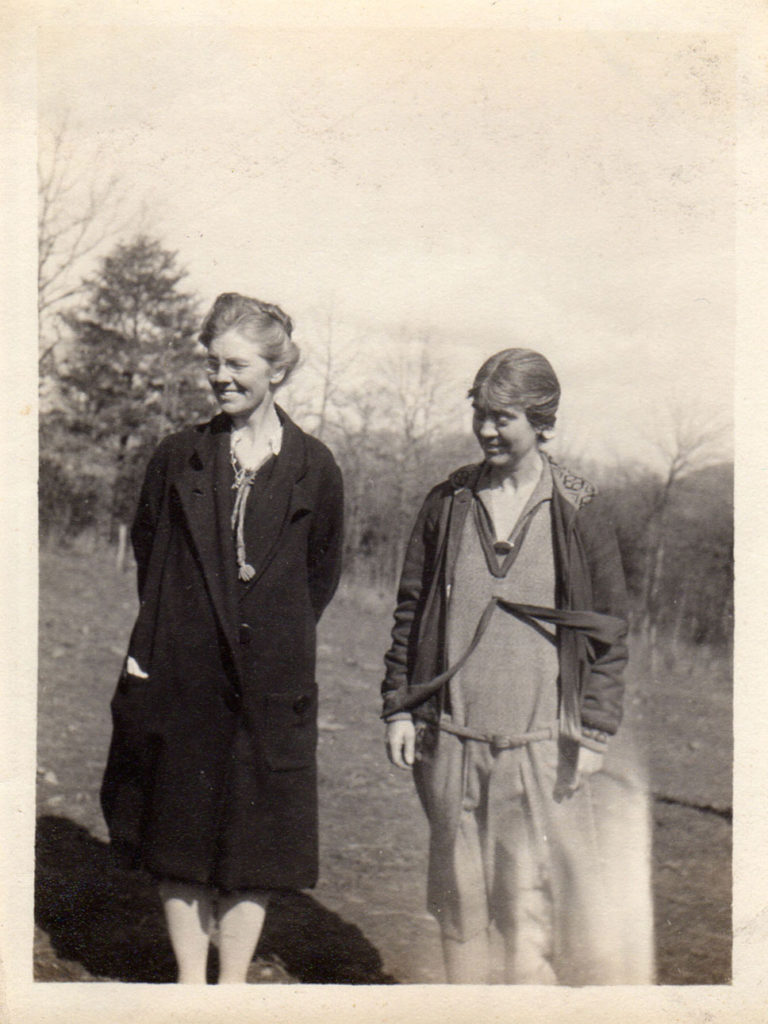

Olive Dame Campbell and Marguerite Butler

Olive Dame Campbell and Marguerite Butler

Marguerite Butler and Olive Dame Campbell holding a lamb on the school campus. Farm work was a major part of the early life of the Folk School.

Marguerite Butler and Olive Dame Campbell holding a lamb on the school campus. Farm work was a major part of the early life of the Folk School.

CP: What do you think Olive Dame Campbell and Marguerite Butler would think of the Folk School today?

AF: I think that both women would be extremely proud of the school. Campbell, in particular, was ambitious and I am sure she would be proud to see the physical growth of the school and the fact that it touches the lives of so many people.

CP: I see that you previously wrote “Olive Dame Campbell, Among the Folk: Education, Experimentation, and Rural Life,” a chapter in North Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times. Can you tell us more about that?

AF: Because of my work on the region’s cultural history, in 2013, I was asked to contribute to a book on North Carolina women. While I was initially asked to write on someone else, I suggested Olive Dame Campbell. Unlike other leaders of the craft revival—Lucy Morgan and Francis Goodrich—Campbell did not write an autobiography. That said, she was a prolific writer. During her lifetime, she wrote three books: one under her own name, one as co-author, and one under her husband’s name. She also wrote his biography, kept a journal of their travels and, independently, wrote numerous articles, speeches, brochures, newsletters, and school reports. In the forty years that Campbell lived in western North Carolina, she collected folk songs, tallied mountain schools, studied Scandinavian education, established a school of her own, organized numerous agricultural cooperatives, wrote several books, conceptualized a craft marketing guild, and organized multiple conferences. Campbell was a major figure in the movement and one without a documented history. I decided her story needed telling.

Woodcarvers at Picnic Tables

Woodcarvers at Picnic Tables

Carvers in the 1940s work outdoors in the shade of a tree. Instructor Murray Martin is at far left. The woodcarving cooperative, later known as the Brasstown Carvers, was one of the school’s first economic development projects. Carvers would receive wood and instruction from the school and the school would then purchase the finished carvings for resale.

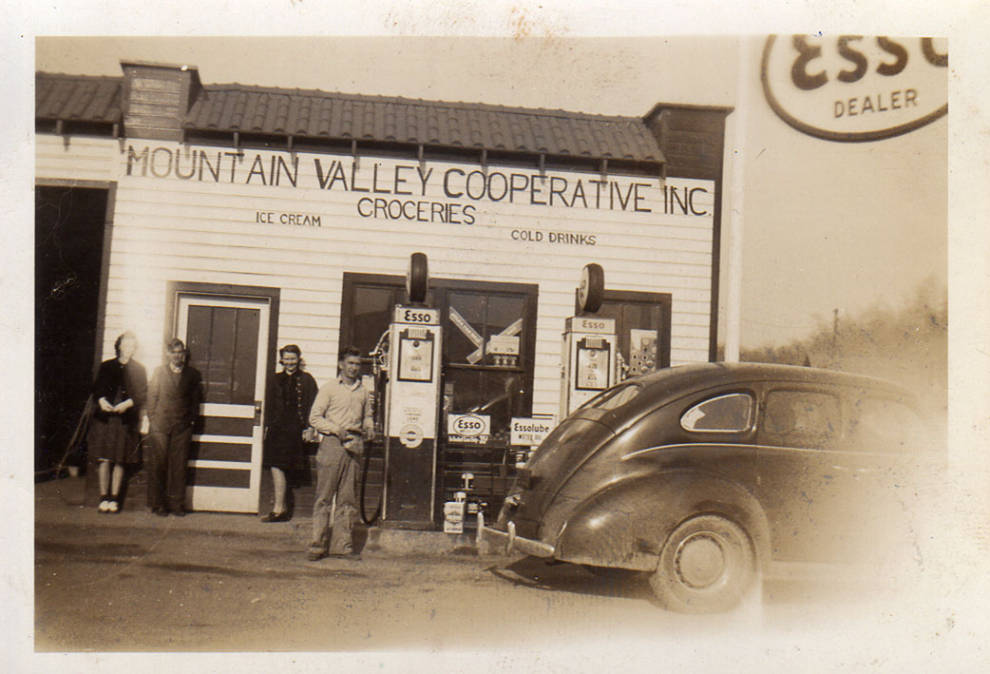

Mountain Valley Cooperative

Mountain Valley Cooperative

The above photograph depicts the exterior of the Mountain Valley Cooperative around 1939. As one of the co-operatives put into place by the John C. Campbell Folk School, the Mountain Valley Creamery provided milk, butter, eggs, and other groceries to the community and was an important source of economic revival for the rural area. The co-operative organization, which started in 1929, was based on the model of Danish co-operative creameries observed by Olive Campbell and Marguerite Butler on their trip to Denmark in 1922. Identified in this photograph are Joe Fisher as the second person and Boyd Scroggs as the fourth person next to the gas pump.

CP: I was surprised to learn how Olive Dame Campbell was involved in creating many cooperatives, groups, and organizations as a way to organize and support communities. Do you think the spirit of service, charity, and community organization is something that is still present in folk and craft schools?

AF: Olive Campbell was truly amazing. The breadth and scope of her work was ambitious. No one has fully documented the cooperatives that she established; their history could be a book in itself. Reading between the lines, I think that Campbell wanted to start a school but, when she looked at the surrounding community, she realized that the school might not succeed if local families were constantly struggling financially. The cooperatives were aimed at helping local families share resources and grow economically. Although Campbell did have personal resources and willing neighbors, it is still amazing that she was able to establish so many cooperatives. The sheer number of co-ops is surprising. The local ones that I could find include Brasstown Savings and Loan Association and Women’s Community Club in 1926, Community Hatchery and Brasstown Farmers Association in 1928, and Mountain Valley Creamery and Handicraft Association in 1929. During her lifetime, several craft revival leaders acknowledged Campbell as initiator of the regional Southern Highland Craft Guild, an organization that continues today. I am also happy to see that the beautiful stone building of the Mountain Valley Creamery is still in use as the Highlander Gallery.

CP: It is especially interesting to think about this in the context of our modern gig/hustle economy of online selling that often puts pressure on hobbies, dabblers, and crafters to sell, not just make. What do you think of contemporary craft in relation to commerce?

AF: In much of my writing, I often quote Allen Eaton, author of Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands, a 1937 text documenting the craft revival. Eaton wrote of judging craft by two measurements: “one by the product itself…the other by the effect of the work on the producer.” To me, this has always meant that we should consider these twin aspects of making craft: the product to be sure, but also the process that produced it. In an article for Studio Potter in 1996, I wrote, “It is process that sustains. The best of process—which I call whole process—makes us want to re-enter the studio again tomorrow.” I do think that Campbell shared these ideas as well. She saw craft as a means to a more meaningful life. In today’s commercial world, it is hard for craft makers to distinguish themselves from the proliferation of things in our lives. Their strength is their connection to their material and to their audience, not simply the making of a thing to be sold.

Early Folk School images and captions courtesy of Craft Revival Project Hunter

Other Related Projects

Fariello’s previously published books include: Images of America: Cherokee; From the Hands of our Elders, a series of three books on Cherokee crafts; Movers & Makers: Doris Ulmann’s Portrait of the Craft Revival, Blue Ridge Roadways: A Virginia Field Guide to Cultural Sites; and Objects & Meaning: New Perspectives on Art and Craft. She was also the art section editor for the Encyclopedia of Appalachia.

Brown-Hudson Folklore Award. “M. Anna Fariello: Folklife Researcher and Museum Curator.” North Carolina Folklore Journal 57.2 (2010): 8-12.

“Rescuing and Digitally Preserving the Cultural Heritage of the Great Smoky Mountains,” The Signal: Digital Preservation, Library of Congress (2014)

About Anna Fariello

Earlier this summer, Anna Fariello was given a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Folk Art Center during the annual meeting of the Southern Highland Craft Guild. Founded in 1930, the Guild is represents over 1000 craftspeople in 9 southeastern states. Fariello was cited for her work at Western Carolina University where, as an Associate Professor, she developed the online Craft Revival archive. She is currently working with Blue Ridge National Heritage Area to develop the Blue Ridge Craft Trails, a project identifying and showcasing western North Carolina craft makers. She began her work in craft as a potter, but her interest in documentation and exhibitions led her into a museum career. In 1999, she was named a Smithsonian Fellow as the James Renwick Fellow in American Craft.

Her textbook, Objects & Meaning: New Perspectives on Art and Craft, published in 2003, was one of the first books that looked at the history and theory behind craft practice, not just its how-to nature. She went on to write the From the Hands of our Elders series, three books on Cherokee arts and crafts. Her many book chapters and articles include “Lexicon of Studio Craft” in Craft and Contemporary Art. In 2018, she published Craft & Community, an early history of the John C. Campbell Folk School. Since 1990, she curated over 30 exhibitions for museums and organizations, almost all focusing on American craft. From Hand to Hand: Functional Craft was exhibited at Handmade in America in Asheville; Iron: Twenty Ten at the National Ornamental Metal Museum in Memphis; and the touring exhibits Movers & Makers: Doris Ulmann’s Portrait of the Craft Revival and ReFormations: New Forms from Ancient Techniques.

Previously, Fariello was honored with a 2010 Brown Hudson Award from the North Carolina Folklore Society, a 2013 Guardians of Culture award from the Association of Tribal Archives and Museums, and a 2016 Preservation Excellence award from the North Carolina Preservation Consortium.

No Comments