18 Nov Highlights From The Archives: The Hogan Family Collection

“Highlights from the Archives” features specific collections from the Folk School’s Fain Archives, which contains thousands of artifacts, photographs, audio recordings, publications, and paper records documenting the history of John C. Campbell Folk School and its context within craft and local history.

Post written by 2025 Archives work-study student Elizabeth (Marly) Toledano.

Today, many weavers rely on books like the so-called “Green Bible” (Marguerite Davison’s, A Handweaver’s Source Book, 1944) or weaving software to plan their patterns. In the 1920s and ‘30s, however, drafts spread differently, often by word of mouth. As a result, there were plenty of regional variations and local idiosyncrasies. Rather than the extensive notes on threading, treadling, and tie-up many contemporary weavers have come to expect, those in Appalachia simply figured out the pattern based on scant notes and trial and error. Such was the landscape when Alice Hogan (1884-1963) and her husband Paul (1884-1944) began tracking down and collecting their extensive set of weaving drafts and drawdowns, recently catalogued in the Folk School’s Fain Archives.

In November 2014, Wally Avett, grandson of Alice and Paul Hogan, donated the Hogan Family Collection to the Fain Archives. The complete collection consists of approximately 250 weaving patterns and related ephemera compiled by the couple in and around Marietta, Georgia, in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the patterns are recorded as “drafts,” consisting of hashmarks denoting the threading. Others are “drawdowns” which Alice painted in bright colors to visualize the woven design.

You may have heard of Frances Goodrich, who embarked on a similar task in the Asheville area before her retirement in 1918. Goodrich collected drafts and drawdowns from women with whom she worked through Allanstand Cottage Industries, the community-based weaving cooperative she established. Allanstand eventually became part of the Southern Highland Craft Guild, which Goodrich, together with Olive Dane Campbell, helped to found. Although there is no evidence that the Hogans interacted with Goodrich or the Folk School, their similar endeavors suggest the significant scope of the Craft Revival in the first half of the 20th century.

While Frances Goodrich collected drafts around Western North Carolina, the Hogans focused on the region of North Georgia where they lived and worked. Alice Paralee Heard Hogan was born to James Lumpkin Heard and Martha Paralee Hudlow Heard in Forsyth County, Ga. Her husband, Ancil Paul Hogan, was born to Sarah Isabelle Maddox and Dr. Thomas Hogan in Canton, Ga. The couple married in 1904 in Ball Ground, Cherokee County, Ga. For 41 years, Paul Hogan worked as a superintendent at the once-famous Canton Cotton Mill. He quit this job in 1939 to start his own mill, which he ran together with Alice, their son, and their niece. By the time they started their business together, the couple had already been collecting looms and patterns for more than 20 years. They put these to use in developing their trademark Kennesaw Mountain Industries.

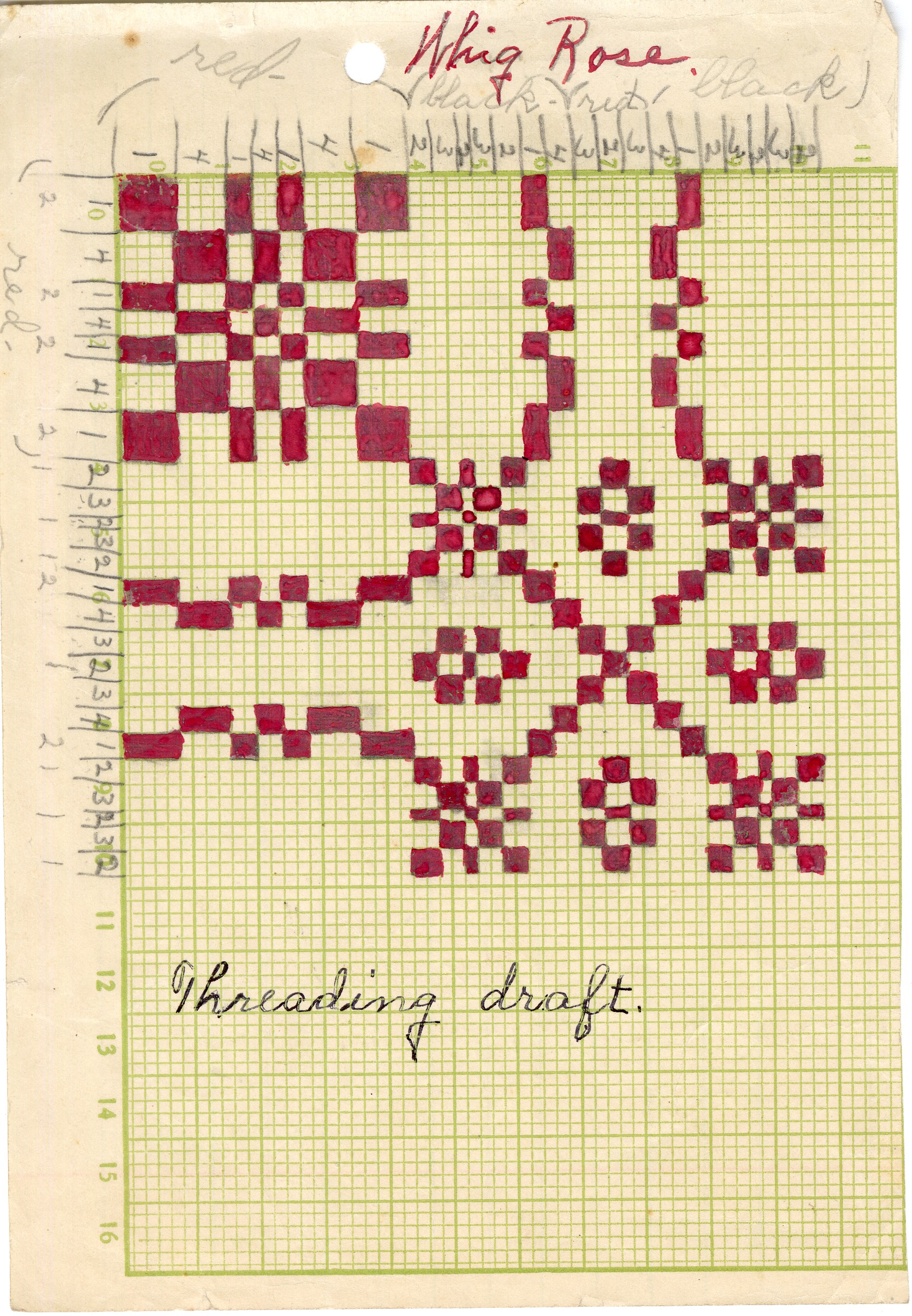

The patterns they collected came from a range of sources, from mountain families and antique stores to early pattern books. It was not until 1944 that Marguerite Davison first published the canonical A Handweaver’s Pattern Book, so many of the patterns featured in this collection would not have been readily available at the time Paul and Alice Hogan were collecting and reproducing them. Several designs the Hogans collected, such as “Whig Rose,” “Jacob’s Ladder,” and “Governor’s Garden,” are referenced in Davison’s book. Others, such as “Cats Tracks and Snails Trails” and “Pine Blossom,” are well-known and highly recognizable to traditional weavers.

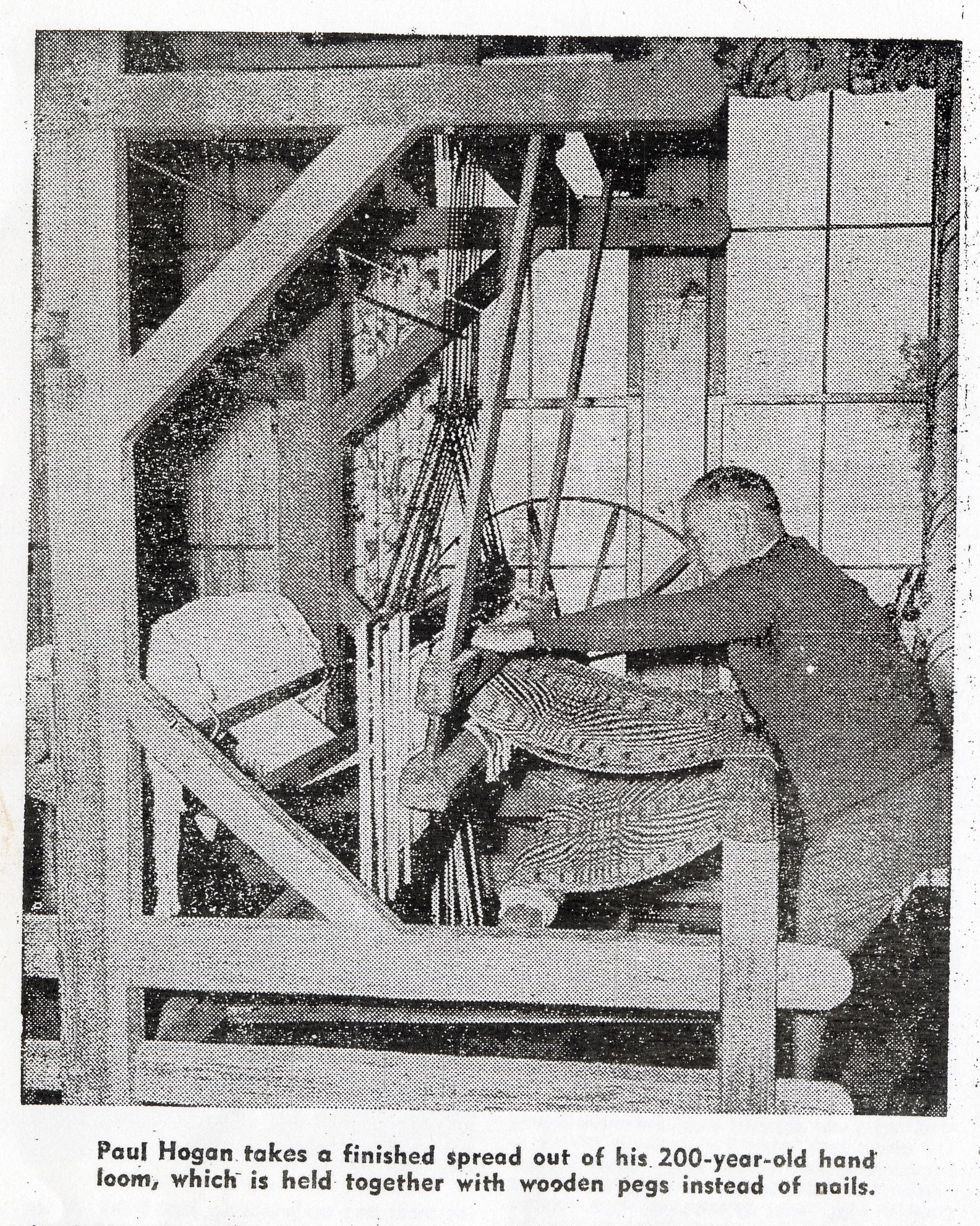

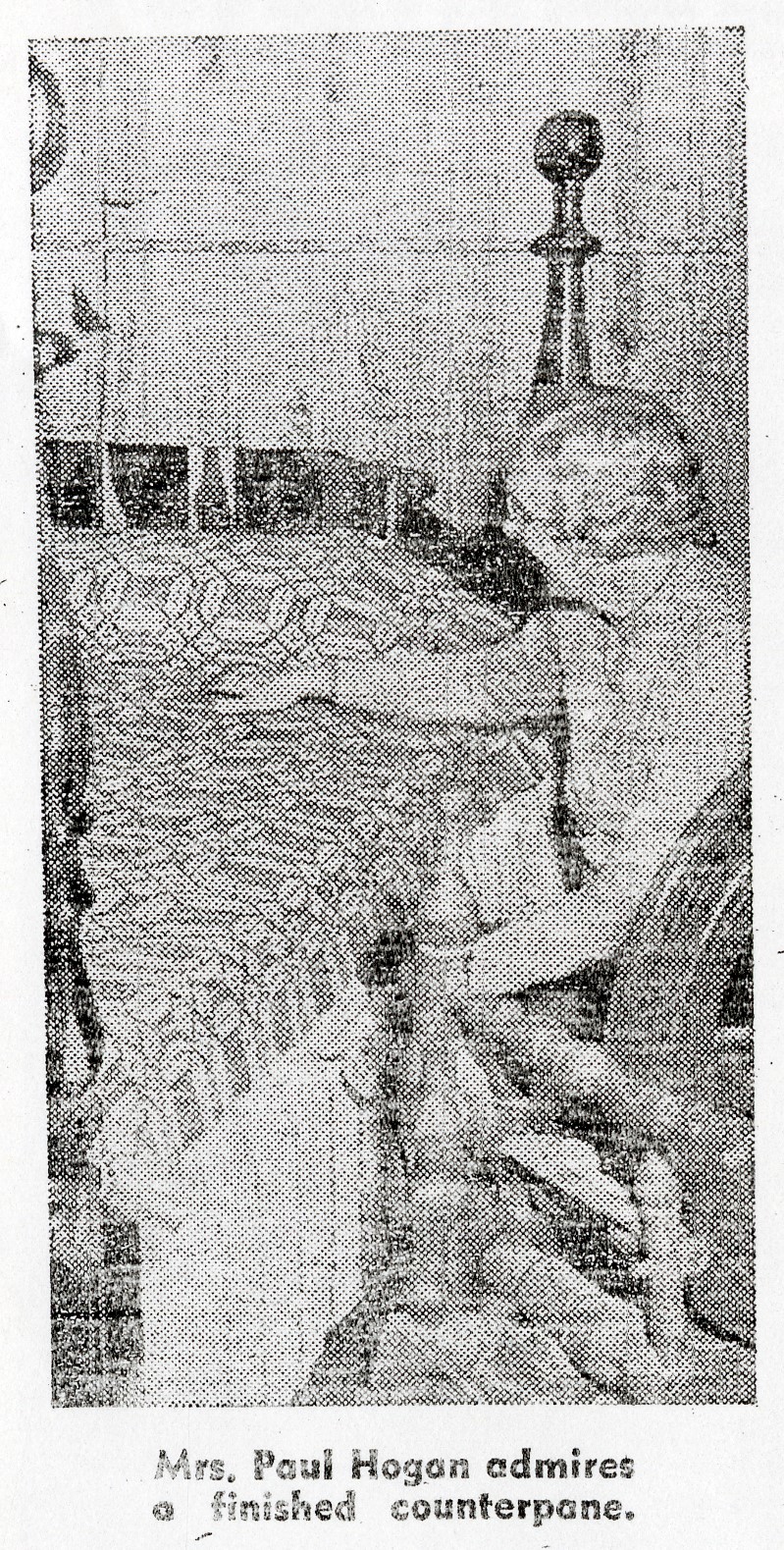

Images from the 1941 Atlanta Sunday Morning article showing Paul and Alice Hogan with their work.

“Whig Rose” and “Pine Blossom” drawdowns from the Hogan Family Collection.

The Hogans often acquired the patterns by knocking on the doors of mountain cabins and copying family coverlets, and reproducing bedspreads passed down in their own family. For example, the Hogans named “Carpenter’s Blocks” for a 95-year-old man named Carpenter whose grandmother’s bedspread they had copied. Some, like “Aunt Betsy’s Draft” and “Mrs. Garisson’s Coverlet Pattern,” seem to have been taken from individuals and acquaintances. “Cherokee Rose” and “Daisy Field” are noted as originating with Mrs. Hogan and likely were her own designs. One labelled “Martha Washington’s Draft” appears to have been copied on a trip to Mount Vernon.

“Carpenter’s Blocks” and “Aunt Betsy’s Draft” drawdowns from the Hogan Family Collection.

“Daisy Field” and “Martha Washington’s Draft” drawdowns from the Hogan Family Collection.

The Hogans used the drafts and drawdowns as the basis for the placemats, rugs, and coverlets they sold. Their mill became popular not only for its products, but as a tourist destination where people could learn about traditional weaving on handlooms. On a given Sunday, as many as 200 visitors would come to the mill, located about two miles outside of Marietta. The Hogans built 10 cabins to accommodate these visitors, and a restaurant called the “Dinner Bell.” The business was well under way by 1941, ad in the Atlanta Journal stating “Kennesaw Mountain Industries have some nice hand-woven novelties to offer for Christmas presents.” As late as 1955, the business was registered with the Georgia Department of Commerce. Little else is known about what became of the company, except that eventually the property became the site of a major freeway between Nashville and Atlanta.

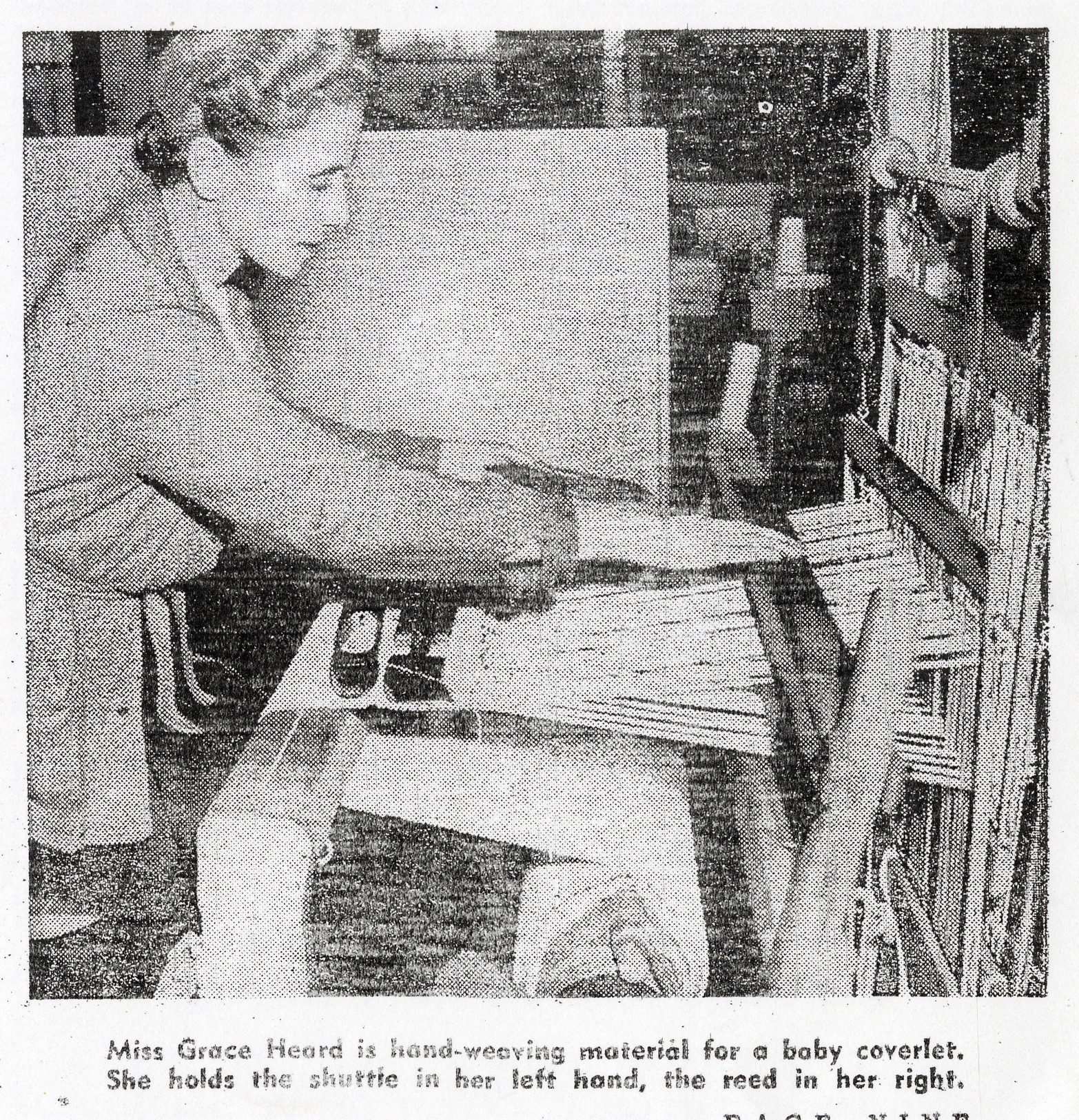

Hogan’s niece, Grace Heard, was a weaver and staff member at Kennesaw Mountain Industries in 1941. In an interview with the Atlanta Sunday Morning, when asked what she thought about while she wove, she said, “Well, old times, mostly, I guess, and the designs and colors the women used to produce. They had dyes made of plants and barks and berries, then – wonderful vegetable dyes…”

At the Folk School, legacy lives on through knowledge. When Wally Avett donated the Hogan Family Collection to the Folk School, he provided both a historical record for the Archives and a valuable, living resource for weavers who take classes here. At the Folk School, weaving students continue the tradition of overshot coverlets based on similar patterns, and, in the future, the Hogan Family Collection will be available to them as a resource.

An image from a 1941 Atlanta Sunday Morning newspaper article showing Grace Heard, niece of the Hogans, at the loom.

“Keep Me Warm” coverlet by Allie Dudley, Folk School Textile & Natural Fibers Coordinator. Based on the “Pine Cone Bloom” draft from the book Keep Me Warm One Night: Handweaving in Eastern Canada.

No Comments